In the rolling hills of rural Rwanda, Beatrice Nyirahabimana makes a living in agriculture. For long stretches of her day, she tends to dairy cows and carefully cultivates Irish potatoes and pyrethrum, small white flowers grown for their insect repellent properties.

Like many of the 500 million smallholder farmers worldwide, poor production, distant markets and limited access to financing meant she regularly felt isolated and struggled to afford necessities for herself and her family.

“Before joining the group, as a family, we had limited capacity to meet all the basic needs,” said Beatrice, referring to the Heifer-supported collective of like-minded women she joined in 2018. “We were constantly living a difficult life.”

This group, the Abihuje women’s self-help group, proved a lifeline for Beatrice and other women in her community who were facing similar challenges and a sense of isolation farming alone. With training and technical support, the women began a united effort to transform their livelihoods through a shared savings-and-loan function.

“It felt good joining the group and it felt even better when I started saving in the group and borrowing,” said Beatrice, who has now borrowed and repaid loans three times, and used the money to grow her herd. “In addition to material gains, I have gained friends and self-confidence and I am now able to interact and network with my neighbors confidently, which was a challenge before.”

When farmers like Beatrice come together like this, when they develop trust and shared goals, when they form fruitful relationships with buyers and traders, they strengthen the intangible “glue” that binds prosperous communities together: social capital.

Social capital is the set of relationships, attitudes and values, such as integrity and mutual respect, that exist in a community and govern interactions among individuals. Simply put, social capital is the positive outcomes of human engagements and the connective trust born from a community’s many networks.

Examples of social capital in society range from the consequential — such as people overcoming their gender bias and sending girls to school, extending financial and psychological support to others in times of crisis or voting in local elections — to the more mundane, like trusting your mail will arrive each day, giving directions to a stranger or returning a lost item.

When cultivated properly, these relationships foster cooperation, social cohesion and collective problem solving — and form the building blocks of a functioning society, from effective government to trusted institutions and equitable markets that ensure fair trade. The positive force of social capital provides individuals, like Beatrice and her fellow group members, with purpose and hope, as well as a solid foundation on which personal and society-wide change can occur.

Shanti Tamang, right, the manager of a woman’s cooperative in Nepal, unloads vegetables from local farmers from an agritransport vehicle. Photo by Narendra Shrestha/Heifer International.

In many of the regions where Heifer works, communities are divided on the basis of social, economic and cultural differences. More often than not, families living in poverty also contend with obstacles like inadequate access to power or water for irrigation, limited employment opportunities, and deeply-entrenched beliefs such as strict patriarchal norms, that often restrict a population’s participation in society and stand in the way of progress.

Developing social capital in these circumstances bands people, families and institutions together with the thread of shared values and principles. For Beatrice and the women of the Abihuje self-help group, social capital also represents the potential to obtain skills, knowledge and resources, such as agricultural equipment and inputs, from their group connections.

In regions characterized by marginalization, poverty, limited infrastructure and inequitable access to financial tools like loans, social capital empowers individuals by identifying common challenges and promoting collective action to overcome them.

For Heifer’s project participants, this involves building relationships and networks, instilling common values, identifying prejudices, and helping group members work toward personal and shared goals in unity.

Increasing the social capital in a community strengthens farmers’ ability to form effective associations like self-help groups, savings-and-loan groups, farmer-owned agribusinesses and cooperatives. These groups bring producers together, improve their access to markets, supplies, knowledge and the capital needed to grow their businesses and, in turn, earn a stable income.

“Social capital helps the people and groups gain wisdom and perspectives, which keeps people’s hearts, minds and actions balanced, focused and productive,” said Buddi Khatri, associate director of social capital development for Heifer programs in Asia. “As a result, they become self-resilient and take ownership of further developments.”

This was certainly the case for Beatrice. After she joined the self-help group, she found herself in the company of other women who supported her growth. The members entrusted each other with their savings and extended loans to women who required immediate financial support for their farming and business needs.

“I am able to get school fees and other school requirements and clothes for children,” Beatrice said. “We have food at home. It makes me proud.”

Social capital is important because it holds a functioning society together — it is built on the understanding that members of a network trust each other, can count on their reliability, and are invested in each other’s success.

Social capital reduces poverty by strengthening the networks within a community that allow for the most vulnerable to take advantage of income-generating opportunities. Mutual respect, trust and shared goals are necessary for economic development and the upward mobility of poverty-stricken families.

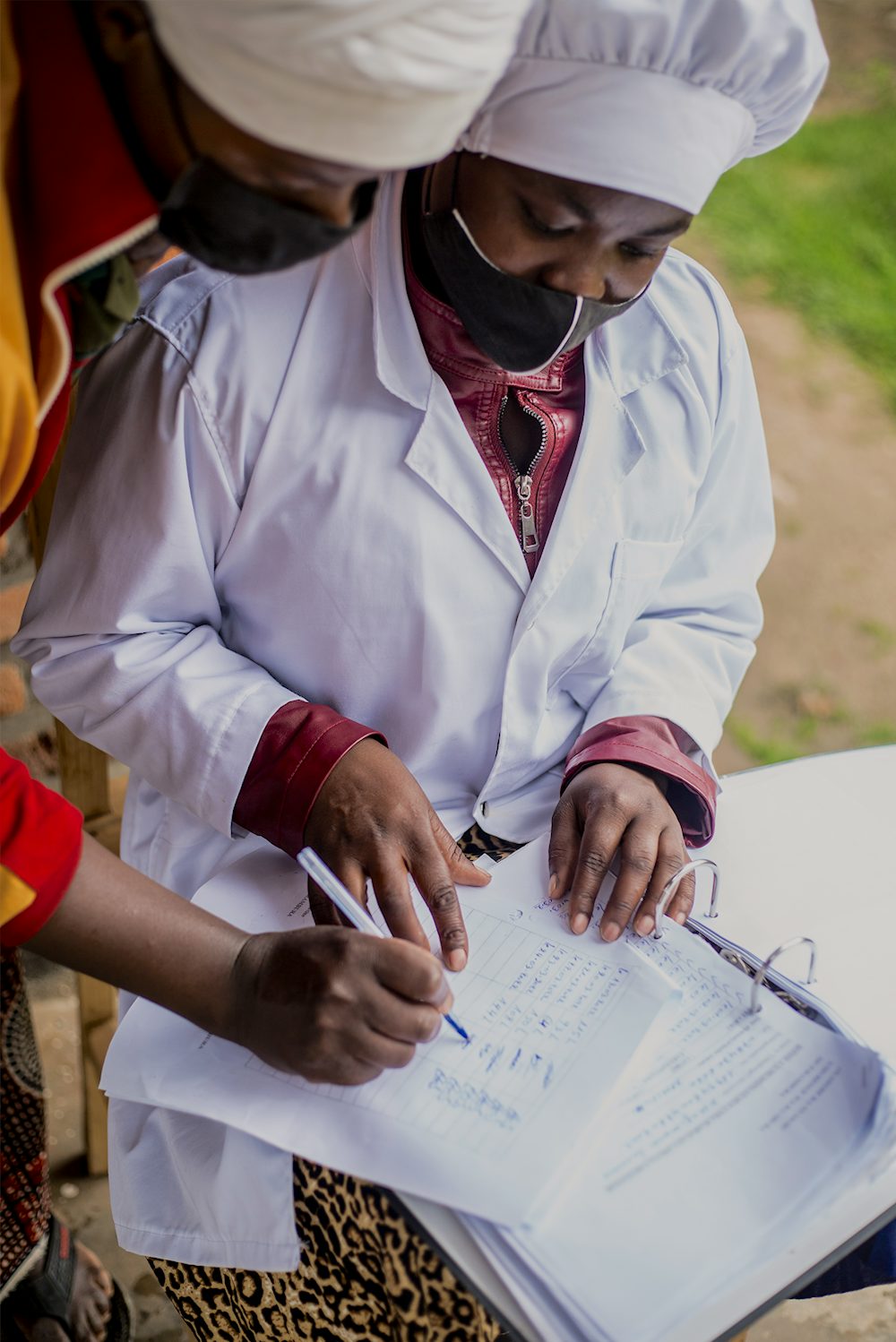

Charlotte Nizeyimana signs a record book at a local milk collection in Rwanda after delivering milk. Collection point worker Grace Nirembere assists. Photo by Jacques Nkinzingabo/Heifer International.

Studies show that developing norms of cooperation, social trust and civic participation are all associated with reduced instances of poverty. Networks and institutions, like efficient markets that pay producers fair prices and financial entities willing to extend loans to smallholder farmers, are built on foundations of strong social capital. In short, more trusting and effective communities are bound by positive interactions and a shared understanding of values.

For smallholder farmers, like Beatrice, who are already struggling to earn enough for their family’s needs, pooling their scarce resources to create a savings-and-loan scheme requires a significant amount of trust — trust that fellow members will repay their loan in full and on time. Social capital is key to developing that trust, and vital to sustainable development.

Heifer strengthens social capital by organizing project participants into groups, reinforcing shared goals and values, providing technical training and physical inputs — such as livestock, seeds or farming equipment — connecting farmers with markets, and supporting community members to take ownership of their vision of the future.

Central to this work is our values-based holistic community development model (VBHCD), which places community groups at the heart of our poverty alleviating development efforts. This model — supported by Heifer’s 12 Cornerstones — is a set of trainings, discussions and reflections that inspire behavioral change among people and create a conducive environment for personal growth.

In small group settings led by a Heifer-trained facilitator, who lives in the community and is familiar with the customs, members learn about and discuss the 12 Cornerstones, including values such as sharing and caring, justice and personal accountability.

“They read, then they close the book and they start to reflect,” said Mahendra Lohani, Heifer’s senior vice president of Asia programs. “What does it mean to me as a family member? As a community member? As a member of my society? Whatever the participants discover is the right answer.”

This community-led development model is “a systematic approach to address the constraints that affect the most vulnerable, marginalized communities,” he continued. “It transforms them in a way to take advantage of the economic forces that exist in their communities.”

Around the world, improved social capital opens the doors for farmers capitalizing on these economic opportunities to improve their incomes and their families’ circumstances.

For Heifer-supported groups in Central and South America, for example, that looks like shared access to improved equipment and technology, like cardamom dryers in Guatemala. During the pandemic, social capital and goodwill between rural farmers and local partners spurred innovation and led to the creation of whole new food system in Ecuador.

Relationships with financial institutions that offer low-interest loans for poultry farmers in Kenya or the savings-and-loans groups in Rwanda are critical to smallholder farmers growing their enterprises. In Nepal, trained community veterinarians are earning an income of their own while keeping local farmers’ livestock healthy. And workshops, led by community facilitators in Bihar, India, create a safe space for local women to reimagine their potential by critically examining the prejudice and social attitudes holding them back.

For Beatrice, now earning almost double than what she did before joining the self-help group, the outcome of social capital means reinvesting her money back into her family and supporting others in her group to grow and prosper.

“There is a difference between working as a group and working alone,” Beatrice said. “I have more understanding of how to live and work together as a family and with others because of the knowledge I gained through the group.”