Like its name implies, a cooperative is an enterprise owned and operated by its members. In simple terms, it’s a people-centered business based on the principle that the power of the group is stronger than the power of the individual.

For smallholder farmers across the world, cooperatives are vital to building profitable livelihoods. In an agricultural co-op, farmers pool their resources, like money, labor and knowledge, and have greater access to markets, training and financial tools like loans. Working together also reduces their operational costs by buying livestock feed or seeds in bulk at reduced prices.

In the work to eradicate rural poverty, cooperatives feature heavily in many of the U.N.'s Sustainable Development Goals. The member-driven enterprises have the potential to promote the fullest possible participation in the economic and social development of local communities across the globe.

Cooperatives take many forms — and names — depending on the communities in which they operate, like “farmer producer organization” or “association.” As an umbrella term, Heifer refers to agricultural co-ops as farmer-owned agribusinesses, or FOABs.

Farm work is intensive, and it’s especially arduous for solo laborers who spend long hours rearing animals or growing crops for minimal returns. Farmers working alone often have little access to high quality seeds and supplies, a lack of financing to expand, and limited training — frequently relying on knowledge learnt from the previous generation.

A cooperative works by enabling individual farmers to overcome these barriers and operate as a collective agribusiness, and this approach is central to Heifer’s work helping people in rural areas rise above poverty and hunger. Across our project areas, Heifer encourages individual farmers to form self-help groups to receive training on financing, loans and values like nutrition, gender equality, and improved animal and resource management.

Sitting together and planning their futures in these groups builds social capital — a trust and shared sense of community between members. They’re no longer individual families struggling to sustain themselves on limited production; they’re a group, bonded by a feeling of belonging and a shared vision.

With Heifer’s guidance, many self-help groups combine to form registered cooperatives or other forms of FOABs. Forming an agricultural cooperative is an opportunity for the group to share knowledge on improved farming techniques, develop a business plan, connect with formal markets and access support like subsidies and technology services from local governments, banks, firms or other supporting institutions.

Banding together also gives farmers access to financial services like savings and loans at nominal interest rates from the cooperative's capital.

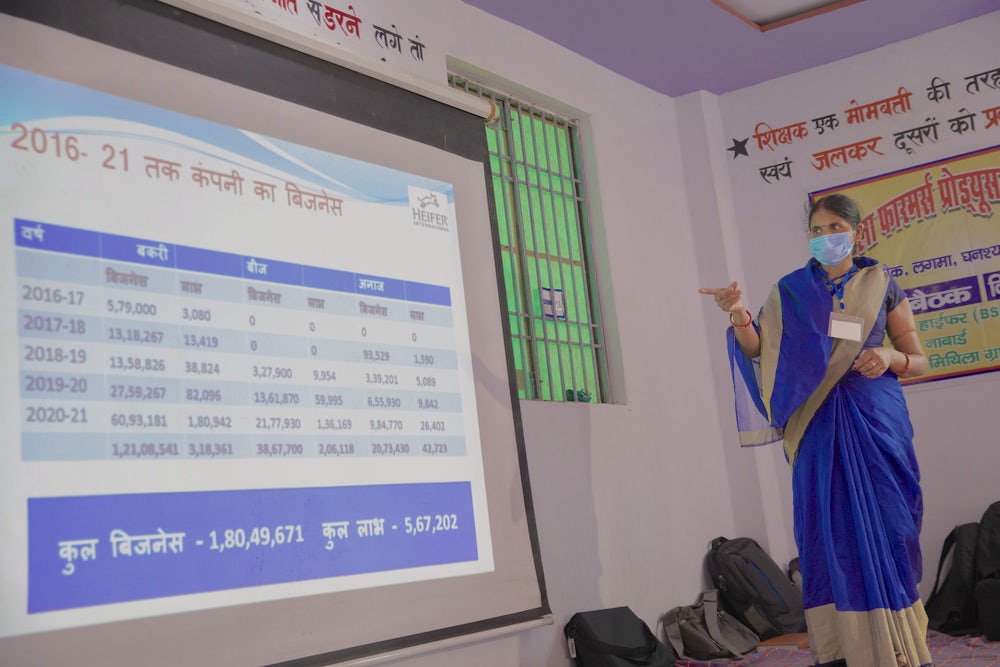

“I did not know what a [farmer producer organization] was — how it works, what a balance sheet [is] — I had no clue,” said Nutan Devi, president of an agricultural cooperative in Bihar, India. After the training, however, everything shifted. “Today, we are supporting goat and seed businesses, working with buyers, managing financial documents and earning profits.”

Cooperatives also work by giving farmers more leveraging power in business negotiations. Whereas buyers likely wouldn’t travel to rural areas to buy two goats from individual farmers, they would travel there to buy 100 goats from a farmer-owned agribusiness. It’s a win-win for farmers and buyers alike.

When cooperatives sell their products to buyers, a portion of the revenue is spent on the co-ops’ operational costs — like administrative upkeep or office space rent — and the rest is distributed to its member-owners.

The global cooperative movement is no small phenomenon. There are 3 million cooperatives on Earth, involving at least 12% of the world’s population, according to the International Cooperative Alliance. And a U.N. study of data from 145 countries put the number of cooperative memberships or clients at over 1 billion.

Against this backdrop, facilitating the formation of agricultural cooperatives underpins Heifer’s work across Asia, Africa and the Americas. In Ecuador, for example, four producer organizations created the country's first farmer-owned online marketplace, harnessing e-commerce to sell food grown by 400 smallholder farmers.

“Working closely with the other associations allows us to share ideas for the site’s improvement and adaptability,” said Nelly Sagbay, member of one of the associations and the site's e-commerce manager. “Cooperation and collective action are key.”

And, in the town of Chahuites in southeastern Mexico, a group of five poultry farmers formed a cooperative to collectively purchase veterinary supplies and products for flock management. Buying in bulk saves them anywhere from 10% to 50% of the usual price.

"With the money I got from the sale of chickens and eggs, I was able to invest in a lot and buy food," said poultry farmer and cooperative member Gabriela Mejía Tapia.

Another example of a cooperative is the Bihani Dairy Co-op in Nepal. It was formed after members identified a need for storage to prevent spoilage of dairy cow and buffalo milk produced in their community. Bihani Dairy invests most of the money it earns back into the community, with the rest reserved for further improvements for the business. The group also used some of its funds to create low-interest loans for struggling farmers.

“We realized that we couldn’t work singlehandedly, that we had to work together,” said Tulsi Thapa, chairperson of Bihani Dairy. “We got to know our sisters. It unites us.”

United in the humanity of cooperation, local farmers around the world are building more profitable and productive livelihoods, improving food security and contributing to healthier and more resilient communities. The values of solidarity, reciprocity and democracy that underpin cooperatives lead to far-reaching and long-lasting change — the kind of change that lifts families out of poverty and opens the doors to leading dignified lives.