The premise, we concede, is an odd one. An underemployed 34-year-old designer plots to escape the anxiety of modern urban existence by plunging himself as deeply as possible into the animal world. The young man’s wholehearted pursuit to become a goat in every way possible¾physically, behaviorally, psychologically¾requires a team of scientists, a shaman, engineers and goatherds, all of whom share expertise to create as authentic a ruminant experience as possible. The resulting book chronicles author Thomas Thwaites’ experiment in full detail, complete with dozens of photos of the author decked out in his goat kit.

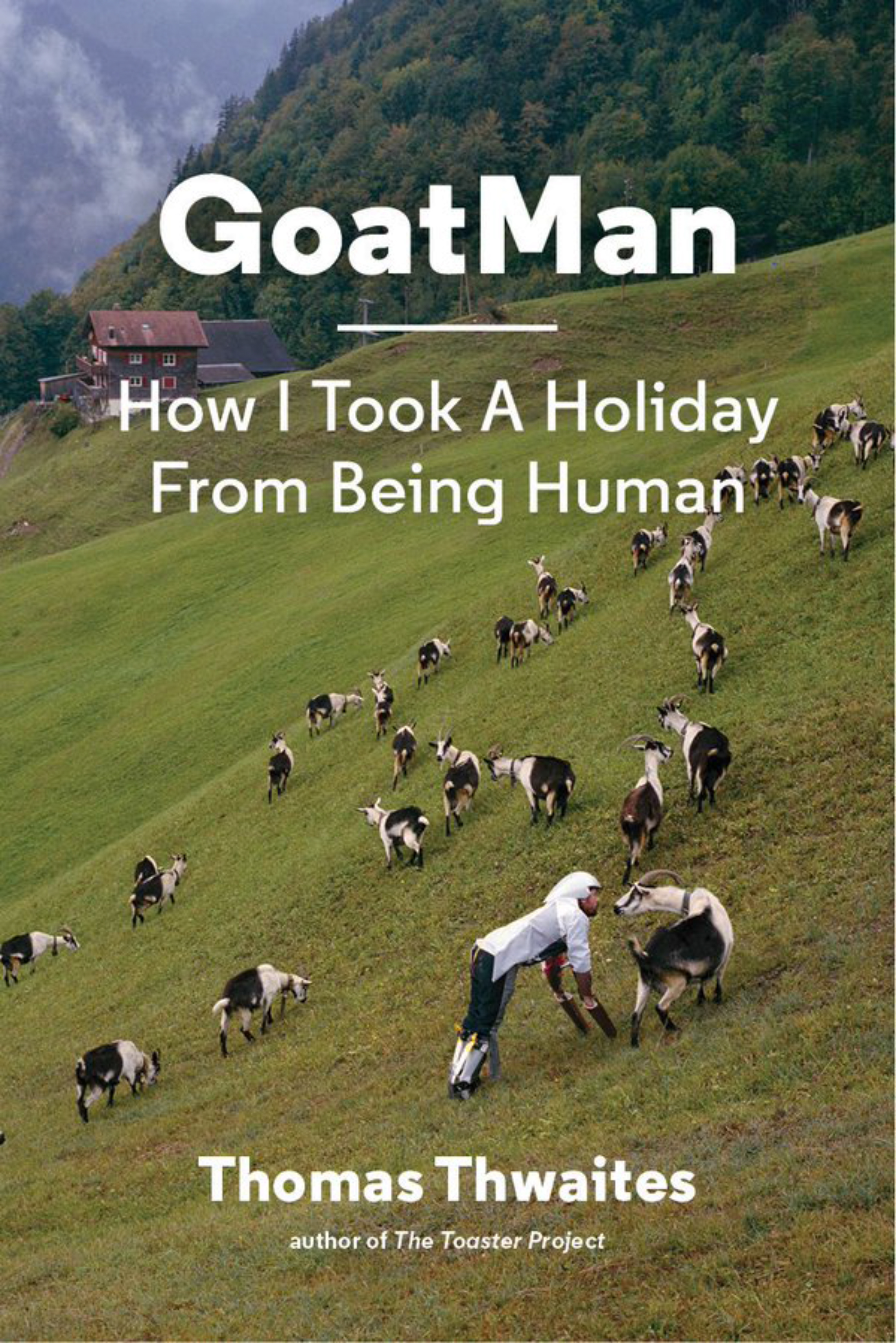

If you’re feeling embarrassed for Thwaites about his four-legged antics already, you can relax. Get past the cringe-worthy cover image of him nuzzling a goat as the two graze on an Alpen mountainside, and you’ll soon discover that the author is in on the joke. So much so, in fact, that it’s hard to take him seriously. Heavy-handed with the knee slappers and puns, Thwaite is a master of the “dad joke” genre despite not yet having any children to embarrass (and if he doesn’t lose the goat suit soon, he likely never will).

Readers might struggle to keep the goofy writing style and unfortunate photos from distracting from a serious question at the crux of the book: What exactly is it that differentiates us from the animals? GoatMan offers an absurdist approach to answering this age-old question. Humans trying on animal characteristics, both physically or mentally, is not a new concept. Thwaites offers a colorful history of human/animal hybridization, from a 40,000-year-old cave carving of a lion/man to a relatively recent drawing of a costumed Siberian shaman channeling deer. Our animist ancestors sought communion with the divinity of other creatures, and hunting cultures sought understanding so they could better track their next meal.

For Thwaites, though, the draw of a grass-fed, pasture-raised lifestyle is freedom from angst. Pressure to succeed, the hectic pace of life in London, no clear path forward: Thwaites pines to exchange this millennial ennui for a carefree gallop through the clover. Simple enough, but he goes all in, even exploring ways to surgically alter his body to make it more goat-like. Luckily doctors could fine no medical means to give Thwaite 360-degree vision or the ability to digest grass with just one stomach (goats have four).

Full goat mode is Thwaites’ singular pursuit, but he proves easily distracted. Readers will topple down lots of rabbit holes to learn interesting factoids that are perhaps only peripherally related, but interesting enough to warrant a side trip. For example, did you know that jockeys used to put goats in pens with horses the night before a big race to keep the horses calm? Jockeys would sometimes steal the competition’s goat to upset a horse, hence the term “get his goat.” To his credit, Thwaites offers up loads of these trivia-night gems.

But while Thwaites’ premise was compelling, his conclusions were not. He seems ultimately to enjoy his few days of goat life, but fails to give it much meaning. In the end, Thwaite comes off more like a stunt man looking for validation than a serious thinker in search of a vacation from the human condition. Animal behaviorist Temple Grandin communed with livestock in a different way than Thwaites, mentally putting herself in their place to improve their lives and deaths by making slaughterhouses more humane. A tough act to follow, to be sure. But is it too much to ask for some sort of epiphany after his months-long pursuit? Ultimately, GoatMan comes through with entertainment value but fails to deliver much of anything else.