This year, Heifer International is celebrating its 75th anniversary. As a part of the celebration, we’re sharing some important moments in our organization’s history.

In the summer of 1955, Heifer Project — now Heifer International — started working with the Prentiss Institute, an African-American junior college and vocational school. It was the start of a 30-year partnership that eventually helped empower families to lead the charge for desegregation in their community.

The partnership with the Prentiss Institute, in Prentiss Mississippi, was one of Heifer’s first full-fledged projects in the United States. Just two months after the relationship began, and in the same state, 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched after being accused of bothering a young white woman. The brutal murder was one of many important sparks of the black civil rights movement, but it’s also a visceral reminder of the context and danger of living as a person of color in that time and place.

Prentiss is the county seat of Jefferson Davis County, named for the president of the Confederacy, and throughout the years, it has been listed as one of the poorest in the country. The Prentiss Institute opened its doors in 1907, a year after the county was created from pieces of surrounding counties.

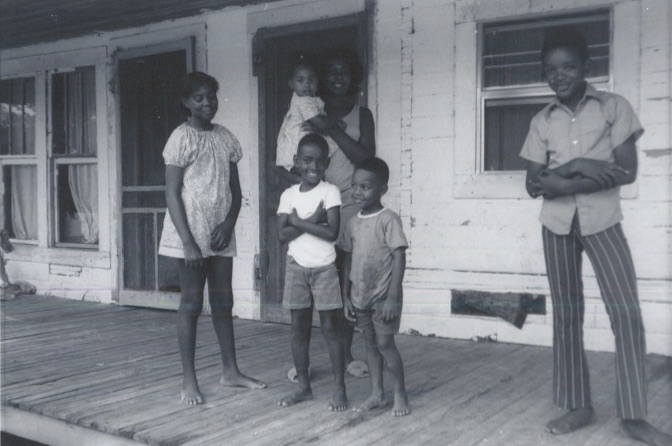

In the early 1900s, Prentiss only had a population of 200 and the institute had to convince parents in rural areas to send their children there. The initial 40 students paid for their education through commodities their families had — eggs, chickens, produce. Through years of perseverance and success, the institute counted more than 700 students and a faculty of 44 by 1953. The school grounds rose from 40 acres to 500, and from one building to 24.

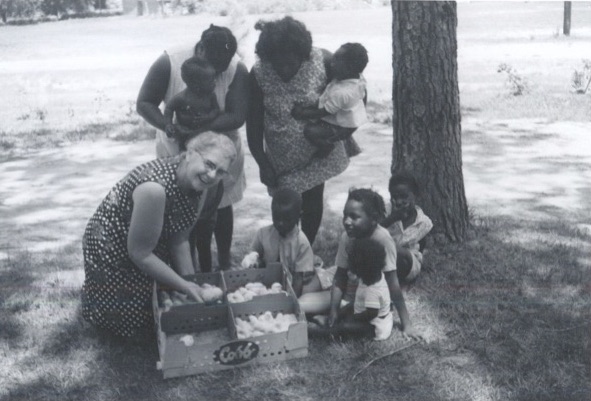

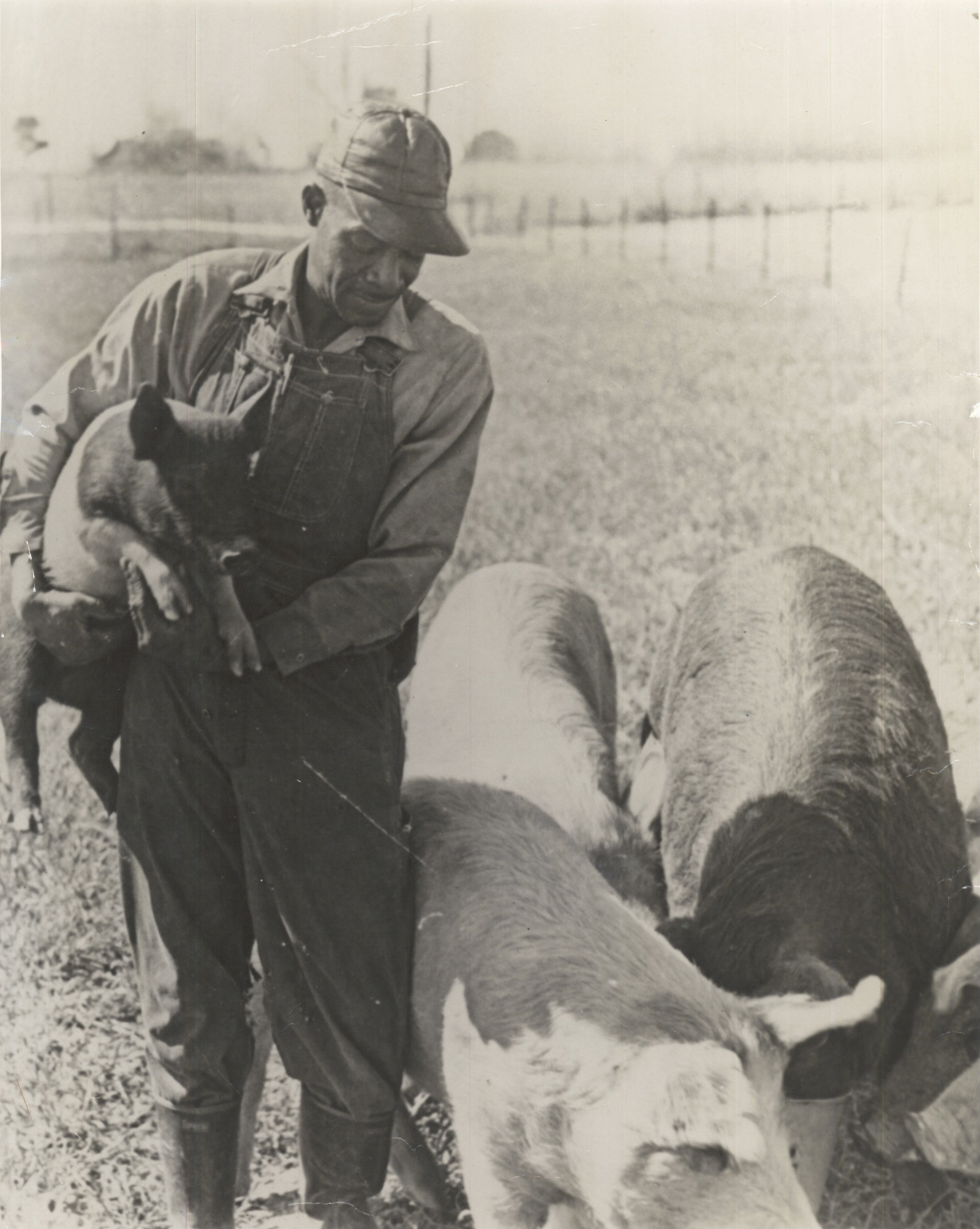

On Christmas Day 1955, State Times reported, “Prentiss Institute, a 48-year-old private junior college and vocational school, received 15 pure-bred heifers last week for distribution to families who want to diversify their farm income but are not financially able to do so.”

According to the news report, upon the arrival of the second shipment of heifers in Prentiss, “the Institute asked white leaders in Jeff Davis County to help them donate some of the animals to white families.”

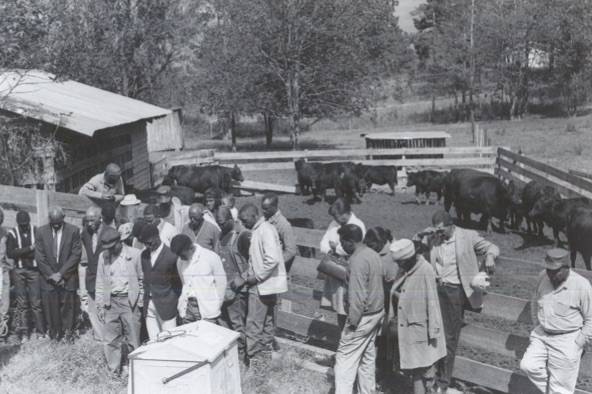

Years later, the Prentiss Institute and Heifer worked together to ensure that black 4-H members could show the animals they received through the project in county and state fairs, something that previously was not allowed.

In the spring of 1968, Willis A. McAlpin moved to Prentiss as a Heifer Project employee to oversee livestock donations and instruct families in animal care and the improvement of agricultural practices. He also managed the 500-acre farm owned by the institute.

On April 4, 1968, McAlpin’s second day on the job, word came that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

“Things were pretty tense for a while,” said Dr. A.L. Johnson, then dean of Prentiss Institute, according to an April 1969 newsletter found in the Heifer International archives. “When Dr. King was killed, violence was in the air. Students were ready to explode any minute in frustration and anger against the white world. Even responsible adults asked themselves, ‘How will I answer my grandchildren when they some day ask me what I did on that tragic night to avenge Dr. King’s death?’”

“Fortunately,” continued Johnson, “Willis McAlpin, the new Heifer Project representative, arrived on campus just the day before. We knew he had come not to get but to give, and that he had left his family and a comfortable home in Iowa to come to Mississippi and show us how to manage our farms better. So we invited Mr. McAlpin to speak at the memorial assembly for Dr. King. His presence demonstrated to the students that white people aren’t all against them, and reminded us of Heifer Project’s help and friendship which has been proven over the years.

“As a result, we got through those days without a single incident of violence and went on to demand and receive equal treatment in areas where we had previously been discriminated against.”

At the time of King’s death, segregation permeated Jefferson Davis County. According to the Heifer newsletter from the archives, African-Americans “could not eat in white restaurants, or sleep in white hotels, or worship in white churches. Even at the Dairy Queen, black children had to wait at the side window while whites at the front window were served first.”

But six months to a year later, things started to change for the better. Jerry Bedford, Heifer Project director of development, wrote: “Unanimously, if not joyously, in response to growing black pressure, white businessmen in the town of Prentiss signed a statement promising equal service to all customers regardless of race. Restaurants, theaters, hotels are now open to everyone. ‘White Only’ signs have been removed from restroom doors, and gas station attendants clean the windshields and check the oil for black customers as well as white.”

Johnson attributed part of the reason for the change to the institute’s partnership with Heifer. “Heifer Project is one of the influences that have helped us bring about this change peacefully,” he said. “Receiving help from Heifer Project strengthened our people’s will to do everything they can to help themselves.”

In Heifer International's 75 years of work, we've worked with farming families all over the world, including the United States. Donate today to support our continuing work to end hunger and poverty while caring for the Earth.

In 1969, public schools were begrudgingly integrated in Mississippi, and enrollment at all-black schools like the Prentiss Institute dwindled. By 1989, the Prentiss Institute closed its doors, ceasing to function as an educational institution. Shortly before that, the partnership between Heifer and the institute came to a close; but the legacy of that partnership lives on.