The moment the plane took off last December, I realized my 10 days in northern India wouldn’t be nearly enough. No matter the train rides and relentless schedule that shuttled me from smog-choked Delhi to the jungles of Odisha to the Rajasthani desert. I flew out exhausted and exhilarated, sure, but still with only a glancing familiarity of the subcontinent.

This is not the first time a country visit left me flummoxed, but there’s a trick for this. Books. A bookshop kiosk in the Indira Gandhi International Airport spilled over with titles for the confused traveler attempting to make sense of what just happened to him. I’d loaded my carry-on with a few titles on Indian culture and history.

This first stab at reading my way to understanding didn’t work, though. The clinical distance of these academic books wouldn’t gel with the India I’d just visited, a country bursting with color and culture, seemingly a thousand nations all jammed into one. Mughal emperors and the British East India Company and a thousand other echoes of history surely underpin what’s happening in India today, but what does that mean for the man serving hot milk tea from a dusty roadside counter? How do thousands of years of history manifest for the veiled, illiterate goatherd women of Rajasthan or the opulent wedding parties celebrating with fireworks outside Delhi’s glitzy high-rise hotels?

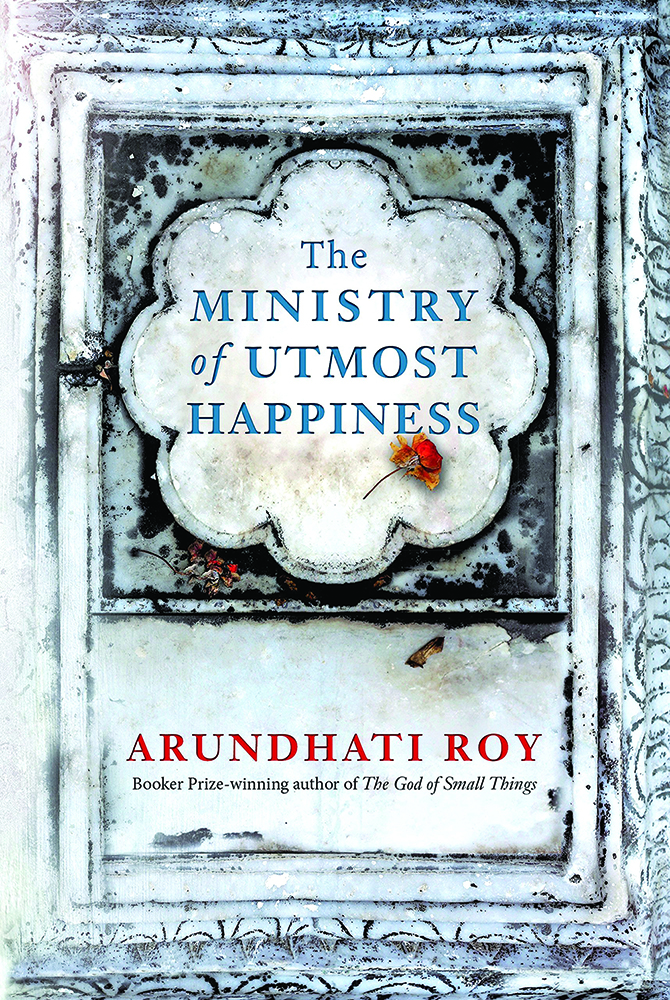

It was time for a novel approach, and the timing was good. Arundhati Roy, an Indian writer who won the Man Booker Prize in 1997 for her first novel, The God of Small Things, released her second novel in June 2017. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness came out to a panoply of mixed reviews, including one from The Atlantic that deemed it “a fascinating mess.” This may not sound like a selling point, but it was a siren song for me. “A fascinating mess” seemed an apt description of the gorgeous, crowded, diverse country I was still trying to figure out.

And it worked. Sometimes a novel captures the feel of a place far more clearly than nonfiction can. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness mirrors India’s clashing confusion of tradition and progress, Hindu and Muslim, wealth and poverty. Like those collages made up of tiny stand-alone images that, when you step back, show you a whole other, larger picture, Roy’s new book pastes characters and vignettes together into a cohesive (enough) whole.

Readers overwhelmed by the multiple characters and myriad storylines can’t say they weren’t warned. A quote that takes up the entire back of the dustjacket hints at the circus to be found inside: “How to tell a shattered story? By slowly becoming everybody. No. By slowly becoming everything.” Roy’s book seems purposefully mish-mashed to capture as big a picture as possible of the tensions in modern India. Some will say Roy’s ambitions were too high here, and the work suffered for it. Maybe so, but it’s still grand enough to have landed her on the Man Booker Prize longlist for 2017, along with other top-notch authors including Zadie Smith and Colson Whitehead.

Roy makes a valiant and mostly successful attempt to give her readers a broad view of her home country as she sees it. In the 20 years between her first novel and her second, Roy kept writing, but stuck to non-fiction works about social issues like the caste system, Hindu-Muslim tensions and the challenges of capitalism. The characters in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness personify a full menu of India’s woes to such a degree that this novel could be a companion piece to Roy’s two decades of progressive journalism. In fact, anyone not fully up-to-date on Hindu nationalism and the push for Kashmiri independence would do well to brush up before cracking this novel, or to at least keep Wikipedia at the ready.

The book’s most colorful character is Anjum, a transgender woman who eschews the modern “transgender” label in favor of hijra, the traditional term for a person labeled as a male at birth but who lives as a female. Like so many of the characters in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Anjum embodies the tension between opposing forces inside India: man and woman, old and new, Hindu and Muslim. The political tensions Roy spent decades focused on in her journalism are personified in Anjum, and in other characters in the book.

Reading Roy’s new book didn’t clear my head about India so much as it helped me to feel better about being overwhelmed by it. The book also helped me pin down some of the dominant modern trends and divisions that shape lives in India today, even as centuries-old traditions and culture keep a strong hold.

Novels can make foreign countries and unfamiliar lifestyles accessible and understandable to us in ways nonfiction can't. If a plane ticket is out of your price range, take a trip to the library instead.