When a cholera outbreak hit the northern part of Cameroon in May 2010, it seemed like a distant problem to the 8,000 residents of Efok, Komo Mvogkani, Nkoltomo II and Nkolbiyem villages. They believed they were far enough from the outbreak to be safe.

However, due to a broken water and sanitation system, the waterborne disease quickly spread to eight of the country’s 10 regions. In just a few months thousands were killed and more than 10,000 became ill. Authorities said it was the worst outbreak in two decades.

Four years later, the outbreak continues to wreak havoc. In May 2014, the Ministry of Health said that more than 250 new deaths were registered in Yaoundé and surrounding towns and villages. Across the rest of the country, cases are reported weekly.

With the absence of a sanitation system and water pipes, as well as humans and animals drinking from the same water source, Efok, Komo Mvogkani, Nkoltomo II and Nkolbiyem villages seemed like the outbreak’s next stop. Miraculously, however, they have been spared. And residents felt the pressure to improve their existing, unprotected wells before their luck ran out.

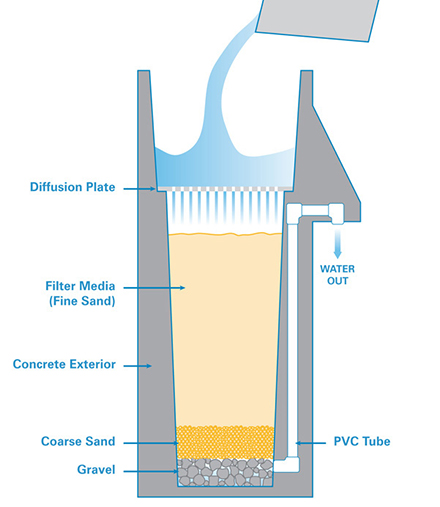

When Heifer Cameroon staff heard about the persistent outbreak and contaminated water supplies in many of the villages, they started to train farmers. While the farmers had already learned how to successfully rear goats, improve crop seeds, adapt effective agriculture techniques, and address social issues, Heifer wanted to help residents improve their water systems. Before long, farmers were constructing and learning how to care for biosand filters, a water treatment system that helps to remove heavy metals, bacteria and viruses from the water supply. It also helps with discoloration of the water, bad smells and unpleasant tastes.

You can help provide families around the world with clean, healthy water.

Biosand filters are inexpensive and relatively easy to take care of, so the four villages easily adopted the system. Efok village constructed and established nine biosand filters in 2010, and Komo Mvogkani, Nkoltomo II and Nkolbiyem followed suit, establishing 40 biosand filters in 2014.

Margarette Eyebe built her own filter and has been using it for three years. “Before the filters, we were drinking water from springs and wells,” she said. “Now, we drink the same water, but it is filtered and clean. It is a very good thing, especially with cholera looming in our district.”

Thankfully, there has been no sign of cholera in Eyebe’s village. “There has been no cholera in Efok,” she said. “Cholera has not come to those who are using filtered water. Many people in the village come here to use the water filter.”

The filters have prevented more than just cholera. In the past, the village was plagued by typhoid fever, dysentery and intestinal worms. But now, thanks to the filters, those problems are largely gone and households spend less on health care.

“We used to spend a lot on diseases like dysentery,” Eyebe explained. “But now we are not getting sick and we are not spending as much as before on medicine or hospital bills.”

Biosand filters are made of concrete columns of sand and gravel. After passing through the filter, muddy water comes out sparkling clean. According to the developers, water filtered through the equipment is more than 97 percent pure. If adopted on a wider scale, biosand filters could become an inexpensive way to provide clean water to millions of rural dwellers who have poor quality water.

“The biosand filter is an appropriate and affordable technology,” Eyebe said. “It ensures access to safe drinking water, especially in rural households that fetch unhygienic water from streams, rivers and wells. Even households that depend on wells will find the biosand filter useful. By using it properly, it will help to eliminate waterborne diseases, especially in children.”

Biosand filters have been shown to remove up to 64 percent of heavy metals and 99 percent of contaminants, such as bacteria and viruses. Besides providing clean water, they have many practical advantages, too. They last for decades and require no electricity. Families can build and maintain their own filters with very little training. Plus, they are easy to operate and less expensive than other filters.

Eyebe filters between 66-79 gallons of water a day. Most is enjoyed by neighbors and passersby, including patients from the nearby government hospital. Other households with biosand filters share their clean water with others, as well. The demand for biosand filters has risen throughout surrounding villages and among area schools. There’s a large interest in the filters being installed on school campuses.

Valantin Ewodo, a retired captain in the Cameroon army, has been drinking filtered water from Eyebe’s for months and plans to build his own one day. He says that although the filter is inexpensive to build, most of his neighbors cannot afford one. “I bought an imported filter several years ago when I retired to the village,” Ewodo explained. “Although it was expensive, it did not last more than two months. My experience is that water that has not gone through a biosand filter is not good. Even if you are not immediately sick, you will be sick later on.”

“Everyone wants to drink good water,” he said. “But how many are willing or able to pay for these filters to be built? I am lucky that I have the means to build one for myself.”

Not everyone in the village has the means to build a biosand filter like Eyebe and Ewodo. According to official estimates, nearly half of Cameroon’s 20 million people live below the poverty line. Many are in rural areas like Efok, Komo Mvogkani, Nkoltomo II and Nkolbiyem, and about 60 percent of them live on less than $1 a day.

Heifer Cameroon has provided training and equipment for 49 filters in four villages, helping to reduce waterborne infections and infestations for more than 8,000 people. In these villages, each filter is shared by an average of 164 people. Even with these new filters, many more families are without clean water.

So the work continues in order to improve the quality of life for families like Eyenga Mbarga of Nkoltomo II. “Without Heifer, we would not have had the privilege of clean drinking water,” she said. She has saved more than $60 a year since she no longer has to pay for typhoid treatments for her children and grandchildren. “We pray that Heifer will bring biosand filters to as many places as possible to help slow the cholera outbreak.”

Story by Ajuh Joel, Livelihoods Development Coordinator, Heifer Cameroon

Edited by Basam Emmanuel, Director of Programs, Heifer Cameroon

Photos courtesy of Heifer Cameroon